The Candomblé’s Orchestra is composed of three main instruments:

The atabaque (Ilu), the “Agôgô” and the Calabash.

There are 3 types of atabaques; the big one (Rum), the medium one (Runpí) and the small one (Lé). These are considered essential for the summoning of Gods. The “nagôs” and “geges” play the leather with the “òghidavis”.

The “Agôgô” is an iron instrument – with two bells, placed over each other, one smaller than the other – played with an iron stick.

The sound of this instrument easily shadows the other ones. When it has only one bell, it’s called gã.

The Calabash is a common calabash covered with a net made from seeds called “Contas da Santa Maria”. During a few years, recently, due to the prohibiton imposed by the police, against the atabaques, the Candomblé Orchestra counts mainly on these Calabashes, also called “piano-de-cuião” or “aguã”.

The chief of the Candomblé adds to the orchestra, as nagô or gege, the sound of adjá, an instrument with one or two long bells that when shaken by the daughter’s ears, help the manifestation of the Orixá and as Angola or Congo, the sound of the “caxixi”, a straw bag interlaced with seeds.

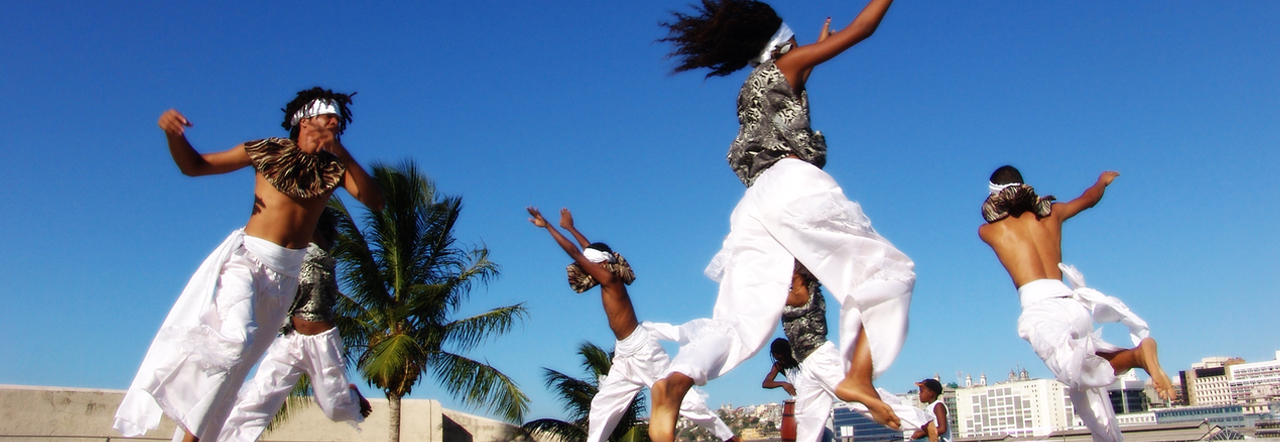

Before the dancing begins, the daughter must treat with reverence the orchestra, with her head to the ground. With the arrival of an “ôgô”, the musicans interrupt their music and offer their salute, with a special beat. The new arrival should, half-kneeling, pass his hands on the ground and then raise it to the forehead, finally touching the atabaques with his fingers. The Orixás, manifested in their daughters, come to pay homage to the orchestra and passes complacently his hands on the heads of the integrants.

Without the atabaque this celebration looses 90% of its worth, for this instrument is considered to serve as the means for humans to communicate and to invoke the Orixás. And still like in Africa, it’s the telegraph, sending the grateful news of the celebration to those from the Candomblé who are afar. It’s the element of the soul of the occasion (still, just like in Africa). And it is really the only appropriate instrument to salute the Orixás, when they “come down” between us mortals or to invoke them. Its presence is necessary to salute the ôgâna, to keep the rhythm, sometimes monotonous, sometimes as flavor, other times dizzying and for the apparently out-of-control times in sacred dances.